One would hope and expect in a society purporting to be civilized, that the negligence of any person or company could not be waived before it happened. Astonishingly, Florida law allows just that: pre-accident releases/waivers barring actions based on the subsequent negligence of the released party.

One would hope and expect in a society purporting to be civilized, that the negligence of any person or company could not be waived before it happened. Astonishingly, Florida law allows just that: pre-accident releases/waivers barring actions based on the subsequent negligence of the released party.

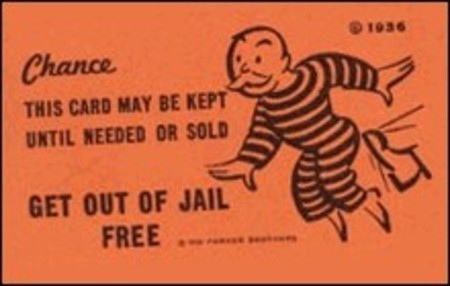

In other words, Florida law sanctions the equivalent of the Monopoly game, “Get out of Jail Free” pass to those whose wrongoing may injure or kill others.

Cognizant of the tremendous consquences of this law – for example, no hope of compensation for a catastrophically injured person – Florida courts have at least decided that contracts which purport to release or indemnify a party for its own negligence are looked upon with disfavor and will not be enforced unless the instrument clearly and specifically provides for a limitation or elimination of liability for such acts. University Plaza Shopping Center v. Stewart, 272 So. 2d 507, 511 (Fla. 1973). Moreover, it may be settled law that the word “negligence” must appear in the release. See, Bender v. Caregivers of America, Inc., 42 So.3d 893 (Fla 4th DCA 2010); Travent, Ltd. v. Schecter, 718 So. 2d 939, 940 (Fla. 4th DCA 1998); Witt v. Dolphin Research Ctr., Inc., 692 So. 2d 27, 28 (Fla. 3d DCA 1991); Rosenberg v. Cape Coral Plumbing Inc., 920 So. 2d 61, 66 (Fla. 2d DCA 2005); and Levine v. A. Madley Corp., 516 So. 2d 1101 (Fla. 1st DCA 1987).

Continue reading

Florida Injury Attorney Blawg

Florida Injury Attorney Blawg