Various Florida statutes require court approval of wrongful death settlements and settlements involving minors (if the amounts received in the aggregate exceed $15,000; See Section 744.301(2), Florida Statutes (2017)). Does this mean that settlements in these situations cannot be negotiated to resolution by the parties without first obtaining court approval? The answer is that the parties can come to a binding agreement before presenting the deal to the court, with the understanding, however, that if the court rejects deal, the parties are unbound.

Various Florida statutes require court approval of wrongful death settlements and settlements involving minors (if the amounts received in the aggregate exceed $15,000; See Section 744.301(2), Florida Statutes (2017)). Does this mean that settlements in these situations cannot be negotiated to resolution by the parties without first obtaining court approval? The answer is that the parties can come to a binding agreement before presenting the deal to the court, with the understanding, however, that if the court rejects deal, the parties are unbound.

Berges v. Infinity Insurance Company, 896 So.2d 665 (Fla, 2004) is the leading case on the subject. It involved the wrongful death of a wife/mother and serious personal injuries to her minor child. After the surviving spouse/natural father of the minor child rejected the carrier’s late tender of its $10,000/$20,000 policy limits, the case proceeded to trial on the wrongful death claim and the personal injury claim. The jury returned a $911,400 verdict in favor of the estate on the wrongful death claim and a $500,000 verdict on the personal injury claim involving the minor. As a result of these combined verdicts, on the theory of bad faith the insured sought to make Infinity pay the full judgments. The jury found that Infinity acted in bad faith.

Infinity appealed the trial court’s judgment and the Florida Second District Court of Appeal reversed. According to the district court, “because Taylor [the surviving spouse/natural father of the minor] had neither been appointed personal representative of his wife’s estate nor been given court approval for the proposed settlement of his minor daughter’s claim, he was without authority to make a valid settlement offer to Infinity.” See Infinity Insurance Co. v. Berges, 806 So.2d 504, 508 (Fla. 2d DCA 2001). The Second District reasoned that the spouse/father’s offer to settle “was merely an expression of his intent to settle once he became authorized to make an offer.”

Continue reading

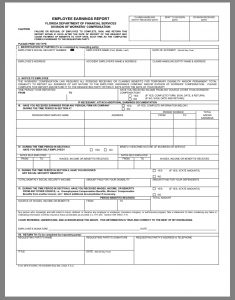

Employers and their workers’ compensation insurance companies (E/C) relish the opportunity to deny benefits to employees injured on the job. One of the most powerful weapons in their ample arsenal is the section 440.09(3), Florida Statutes drug defense. It reads as follows:

Employers and their workers’ compensation insurance companies (E/C) relish the opportunity to deny benefits to employees injured on the job. One of the most powerful weapons in their ample arsenal is the section 440.09(3), Florida Statutes drug defense. It reads as follows: Florida Injury Attorney Blawg

Florida Injury Attorney Blawg